Election nights occur in an atmosphere of exhaustion and relief as our presidential campaign cycles have grown longer. Ask people how they feel on election eve, and you’re likely to hear, ‘I just want it to be over.’ We don’t know if a winner will be announced on November 5, or later. But eventually, there will be a winner, and at whatever point either Donald J. Trump or Kamala Harris steps up to the victor’s podium, their words will set the tone for the coming days and years.

What do the American people want to hear—no matter who is standing there? As a passionate student of our great nation’s remarkable history, I can say they want to hear a message of unity, not division.

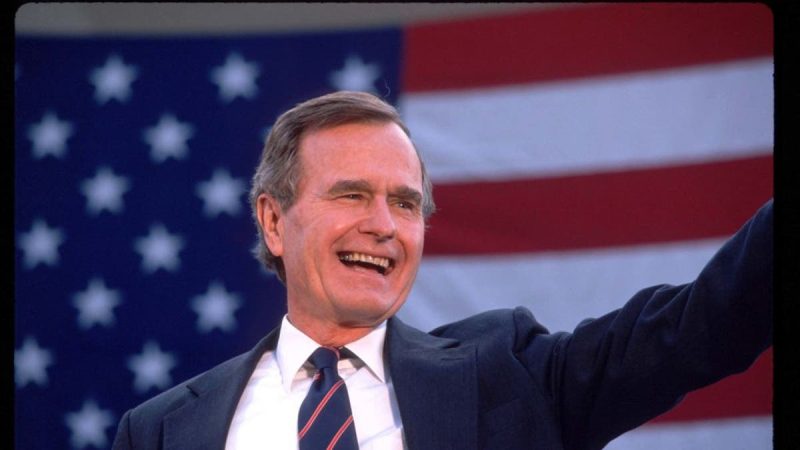

Our forty-first President, George Herbert Walker Bush, was not known for his soaring oratory. However, on the night of November 8, 1988, after winning the presidency, he struck an eloquent note as he shifted from campaign to governance. ‘A campaign,’ he said, ‘is a disagreement, and disagreements divide, but an election is a decision, and decisions clear the way for harmony and peace.’

It struck me that the ability to distinguish between the divisive nature of a campaign and the pragmatic unification demanded by governance was a perfect description of the democratic process first executed by the Founders. Bush was saying that he knew people were feeling bruised from the fight, but he hoped they could move on to work together for the good of the nation.

Calls for unity have been a common thread for election night speeches, no matter how divisive our campaigns.

On November 5, 1952, Dwight Eisenhower learned he’d won the election, and began to make his way to the ballroom where his supporters were gathered. He had just replied to a gracious concession telegram from his opponent, Adlai Stevenson. When he arrived in the ballroom, Eisenhower read his response to his supporters. ‘I thank you for your courteous and generous message. Recognizing the intensity of the difficulties that lie ahead, it is clearly necessary that men and women of goodwill of both parties forget the political strife through which we have passed and devote themselves to the single purpose of a better future. This I believe they will do.’ Eisenhower then cautioned the crowd that the only way to succeed in the presidency was as a united people. ‘Let us unite for the better future for America, for our children, and for our grandchildren.’

Not every president-elect, flush with victory, reaches out to the other side, but most do. Probably the most dramatic case was Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in 1864, while the nation was at war. The war showed no signs of abating, and the future was uncertain. Unity seemed impossible.

Speaking to a crowd, Lincoln noted that it had long been a question, now more urgent, whether the nation could be strong enough to maintain its existence in the worst emergency. He noted that the election ‘has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election in the midst of a great civil war. Until now, it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows also how sound, and how strong we still are.’ Lincoln asked his supporters to extend goodwill to their opponents and spoke of his hope that a unified nation could endure. The war ended the following year.

Unity did not come easily after the war, and the years after the assassination of Lincoln were tumultuous. In 1868, the Republicans turned to General Ulysses S. Grant, the hero of the war, believing he was the one who could bring the nation together. Grant was a reluctant candidate, but he was clear about his mission. His written acceptance of his nomination contained the line that would become his rallying cry as president: ‘Let us have peace.’

There have been other contentious eras. When Richard Nixon stood before supporters late on the night of November 6, 1968, to declare victory over Vice President Hubert Humphrey, the war in Vietnam was at its height, and masses of antiwar demonstrators filled the streets. The election had been bitter, and many people believed the foundations of democracy were in jeopardy.

Once again, there was doubt that unity was possible. But that night, Nixon told a story about unity. On the trail, he said, he’d seen many campaign signs. ‘Some of them were not friendly, and some were very friendly. But the one that touched me the most was one that I saw in Deshler, Ohio, at the end of a long day of whistle-stopping, a little town. I suppose five times the population was there in the dusk, almost impossible to see—but a teenager held up a sign, ‘Bring Us Together.’ And that will be the great objective of this Administration at the outset, to bring the American people together. This will be an open Administration, open to new ideas, open to men and women of both parties, open to the critics as well as those who support us.’

Conciliatory gestures by the victors are important, but so are offers of support by those who lost. In defeat, many presidential hopefuls stand at the podium, crushed by the loss but holding up their heads along with the principles of democracy. Some can still inspire us.

‘The Nation has spoken,’ Alf Landon wrote to Franklin Roosevelt on November 4, 1936. ‘Every American will accept the verdict and work for the common cause of the good of our country. That is the spirit of democracy.’

In 1948, Thomas Dewey, who might have been shocked to lose since the media had declared him the winner at one point during the vote count, conceded to Harry Truman with these generous words: ‘My heartiest congratulations on your election and every good wish for a successful administration. I urge all Americans to unite behind you in support of every effort to keep our nation strong and free and to establish peace in the world.’

And Walter Mondale, after a humiliating landslide loss to Ronald Reagan in 1984, spoke truly inspiring words about who we are as a nation—articulating the essence of America: ‘Again tonight, the American people, in town halls, in homes, in fire houses, in libraries, chose the occupant of the most powerful office on earth. Their choice was made peacefully, with dignity and with majesty, and although I would have rather won, tonight we rejoice in our democracy, we rejoice in the freedom of a wonderful people, and we accept their verdict. I thank the people of America for hearing my case.’

Reagan, in his 1984 election night remarks, spoke about the higher calling, shared by citizens and candidates alike. ‘Here in America, the people are in charge,’ he said. ‘And that’s really why we’re here tonight. This electoral victory belongs to you and the principles that you cling to—principles struck by the brilliance and bravery of patriots more than 200 years ago. They set forth the course of liberty and hope that makes our country special in the world.’

The reminder of who we are and who we will become has special meaning on the eve of the 2024 election. On July 4, 2026, about halfway through the next presidential term, we will celebrate the 250th anniversary of America, the date when the founding document of the nation, the Declaration of Independence, was signed.

It was the beginning of the United States of America. Unity is in our name.

Bret Baier is a New York Times bestselling author of five presidential biographies. Click here to visit Bret Baier Books.

Get to know Donald Trump’s Cabinet: Who has the president-elect picked so far?

Since winning the election last week, President-elect Donald Trump has begun evaluating an…