Approximately 227 years ago, in 1797, George Washington – our first U.S. president – also became the first U.S. president to voluntarily cede the presidency to his successor. At the time, this was unheard of. For much of human history, power transitions were messy, violent affairs.

The list of European wars of succession runs into the hundreds, with kings and emperors serving for life, only to have their heirs mire entire nations in bloody conflict. At the time Washington submitted his resignation, Bavaria and the entirety of Austria had only recently emerged from such wars.

A contemporaneous revolution in France was engulfed in terror and turmoil. Africa and Asia were plagued by near constant conflict. And five of the 10 deadliest wars in history were Chinese civil wars, claiming tens of millions of lives.

America had been founded, in part, as a rebuke to all that terror. The Founders rejected monarchy – the idea that God had anointed any man or a family by birth to rule by violence over others. They instead embraced a radical idea: people are endowed by their Creator with inherent, unassailable worth. That Creator has given them individual rights – among them ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ And government exists not to enforce the power of autocrats but to guard the rights of individuals.

For the first time in history, a major power was formed on the idea that government exists ‘of, by, and for the people.’ Further, those intended to lead that government were simply stewards of the entities erected to protect the peoples’ sovereign rights. When representatives’ terms passed, they are not to appoint their heirs or cling violently to the wheel of state. They are to, like Washington’s spiritual predecessor Cincinnatus, lay down their swords and peacefully convey power to those who will then serve in their stead.

At least three times Washington had an opportunity to personally derail this project. During the revolution, he was granted nearly unlimited authorities – akin to those of the Roman dictators. Many suggested that once victorious he should ascend as king, a suggestion he firmly dismissed. Several years later, his soldiers and officers proposed a similar ascent to power only to be once again rejected.

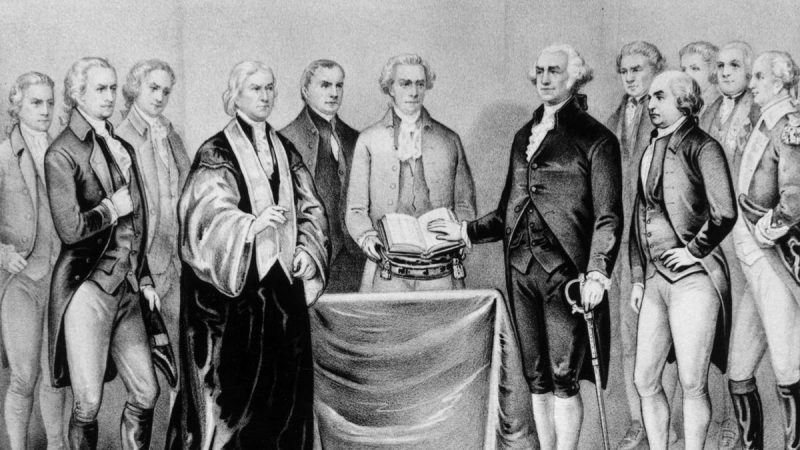

And finally, after the Congress that established our modern Constitution concluded in 1787 and the states subsequently ratified the document, Washington was the first (and last) man to take the presidency by unanimous consent in 1789. He set all the precedents of the office – including adopting humbler titles and dress then others suggested and dramatically limiting his own powers. Then after only eight years, he voluntarily (and to the surprise of all) decided to retire… setting a precedent of two-term presidencies that would endure until Franklin Roosevelt.

King George III, upon hearing of Washington’s plans to retire, reputedly said, ‘If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.’ He was. More than that, he became one of the greatest men in history. Founder of a nation. General of an army that won an unwinnable war. Unquestioned and universally admired civil leader. The one man in these new United States who could have pulled the fledgling republic together.

And the one man, who through his restraint and civility cemented its grand traditions, allowed it to embark on history’s most important experiment in self-governance, and empowered it to blossom into the world’s most powerful country.

So admired was Washington that his farewell address, apart from the Bible, was the most popular book in America between 1797 and the Civil War.

When he retired, it was unthinkable that a man of such power would relinquish it for the good of others. But he did, and in so doing set a precedent that America and her leaders were forever committed to the peaceful transfer of office, limitations on the nation’s executive, and acceptance of the democratic process. Moreover, that single example and the radical growth, innovation and prosperity it unleashed revolutionized systems of government around the world.

Today, U.S.-style representative government is more common than not. Peaceful transfer of power is more common than not. Billions now live empowered over, not crushed under, their leaders. And self-governed societies are typically richer, more beautiful and more powerful than their autocratic enemies. That is a human triumph. It is a spiritual one. It is also one for which our nation’s Founding Father deserves no small measure of praise.

The United States is now approaching its 250th anniversary. We transformed the world. We’ve gradually worked to address the evils and imperfections that remained once the initial revolution was complete. We remain the richest, most powerful, most pluralistic, and freest nation in history. We have been the ‘city on a hill’ our leaders so longed for us to be.

With the help of our democratic allies, we slew the fascist and communist monsters of the 20th century and created a Pax Americana that helped lift billions out of poverty and made the post-WWII era (apart from the civil horrors of Stalin and Mao) history’s most peaceful. And in our 248th year, we will once again transfer power from one executive and Congress to another, I pray, with peace.

But we all feel the Republic is frayed. The constitutional limits laid out by the Founders and guarded by our forebears have been stretched and strained by those who, as Lincoln once articulated, ‘[thirst] and [burn] for distinction; and… will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen.’

Our citizens are now more diverse and divided than ever. Our most recent decade has been pockmarked by violence, riots and turmoil. And our elections – so fundamental to the persistence of self-governance – are plagued by delays, disruptions and widespread questions of legitimacy.

Will we endure? In 2024, it is an open question. No democratic republic has persisted this long. We are in uncharted waters. And history has shown us that even those governmental systems most thoughtfully constructed – America’s first among them – rely on great leaders to eschew the temptations of power and embrace the humility of service.

As we approach the election of Washington’s 46th successor we’d all be wise to consult his farewell address. We’d be wise to be skeptical of power, to demand restraint from our leaders, to remind those who govern that they are servants not lords, and to demand integrity and civility of those from whom great office passes. We should insist on a government of rights not rule. And we should, as Washington so encouraged, ‘Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all.’

Our elections are a sacred right and responsibility. Let’s approach the last poll before our quarter-century celebration with integrity, enthusiasm and reverence. Let’s pray those who emerge victorious do so with honor, humility and a deep dedication to the character and principles our founder so aspired to. Let’s hope they lead, like another world changer, ‘With malice toward none with charity for all.’

Let’s vow to treat our fellow citizens with love and respect when the election ends. And let’s hope those who hand over the reins of state do so in the grand tradition of a great man who showed us that true courage and character are shown not so much in claiming power but in gracefully letting it pass away.

Putin mulls striking Kyiv with new hypersonic missile that can reportedly reach US West Coast

Following an overnight missile and drone attack by Russia targeting Ukraine’s key energy i…